Essay written by Rachael Crabtree giving an insight into the historical context of Philip Sayer's 'Manhattan in Moscow' photographic series, currently on display in our main gallery until 19 March.

‘Manhattan in Moscow’: The history of Stalin’s tall buildings

by Rachael Crabtree

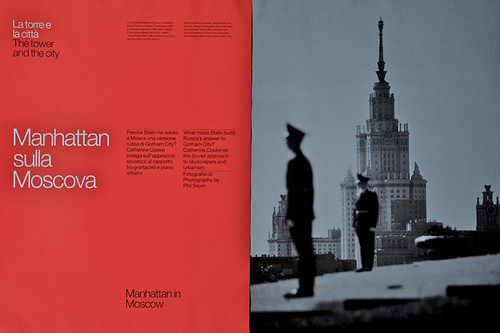

The collection of Philip Sayer’s photographs currently being exhibited at Marsden Woo Gallery, London, depicts seven ‘skyscrapers’ in Moscow, which were the product of Stalin’s ‘Tall Buildings’ programme of the 1940s and 50s. The photographs were originally commissioned for Domus, the Italian architecture and design magazine, for an article written by Catherine Cooke, one of the world’s leading experts on Soviet avant-garde architecture and socialist urban planning.[i] In the article, also entitled ‘Manhattan in Moscow’, Cooke asks, ‘What made Stalin build Russia’s answer to Gotham City?’. Sayer’s accompanying photographs give some visual clues that could answer this question.

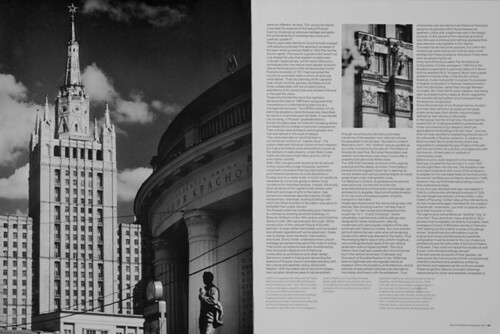

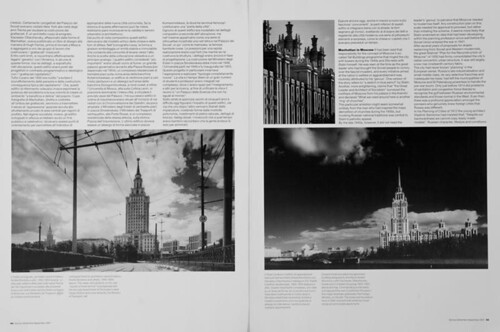

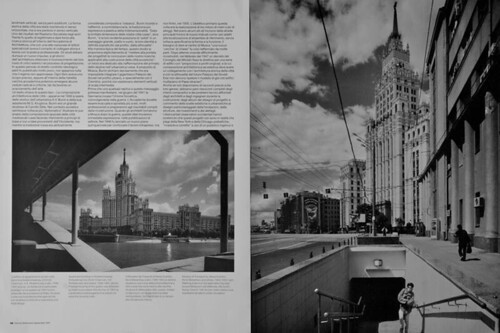

His expert mastery of the black and white photographic form captures the brooding architectural dominance of these colossal structures, which include the 27 storey Foreign Ministry, 24 storey Transport Ministry, the 240m tall Lomonsov Sate University, and more hotels, residential and administrative buildings which encircle the city of Moscow. Each of these striking images has been crafted using traditional photographic processes, demonstrating not only the discerning eye of the photographer, but also his careful hand. An awe inspiring, and often intimidating architectural presence is conveyed in these photographs, a feeling which was present when the buildings they depict were first built half a century before the photographs were taken. Cooke reports that ‘Muscovites who were then children tell how people just went to stare’.[ii]

Up until the late 1940s the fabric of the city of Moscow had consisted of mainly low rise, nineteenth century buildings. The city was in need of modernisation even before the First World War; it was largely problems of sanitation and congestion that forced Russian liberals to ‘recognize the gulf between Russian environmental standards and those normal in the west’.[iii] Due to the well known upheaval in Russia after the 1917 Revolution, and the many economic and social complications that arose with it, it was not until 1935 that Stalin drew up the ‘Plan for the Reconstruction of Moscow’, in which the city’s radical-concentric structure was consolidated, after he reportedly remarked, ‘What we need round here is another ‘ring’ of churches’.[iv]

As Cooke points out in her article, ‘This particular ambition might seem somewhat unlikely from the man who had inspired the mass demolition of churches during the 1930s, but revoking Russian national traditions was central to Stalin’s patriotic appeal.’[v] The 1935 plan was ‘a mixture of the urgently practical and deeply symbolic’, although its realisation was put on hold after the Soviet Union entered the Second World War in 1941.[vi]

As in Europe after 1945, Soviet Russia’s victorious national pride and optimism were combined with a psychological exhaustion that needed to be both sublimated, and expressed materially. A tradition of the Russian state was to erect landmark buildings that marked its victories, and so the 1935 plan took on an even deeper cultural significance in the late 1940s, as it came to represent victory of both the Communist state in itself, and its success in war. The widening of narrow streets and dramatic raising of building heights were to be the built symbols of the USSR’s victories, and an expression of its new found power on the world stage.

Although intended to symbolise the modernisation of Russia, Stalin’s superstructures did not align with the modernist aesthetic of other earlier post-revolution artistic and architectural forms. Social Realism, developed under the leadership of Stalin in the 1930s, legitimated a certain historicism within new architectural designs. Russian architectural tradition was predominantly classical, and these new large-scale buildings drew on the authority of the past to display the power and dominance of the Soviet state.

Compositionally the structures that materialised as part of the ‘Tall Buildings’ plan were largely derived from churches and defensive towers. Architects deployed the iconography of the stepped form to symbolise an assembly of smaller units creating a soaring, collective whole, and although this Communist rhetoric is carried through all of the buildings, their resemblance to pre-war New York ‘capitalist sky-scrapers’ has been described as ‘nothing more than plagiarism…post-rationalised to a gullible public’.[vii]

It is with the knowledge of later events in Russian history that these striking architectural representations of Social Realism, although fuelled by optimism for the future, can be seen as huge exercises in Stalinist propaganda. Philip Sayer captures the complex history of these immense, magnificent, highly symbolic constructions - as awe inspiring feats of engineering, as anti-monuments to a failed optimism, and as sinister markers of a dominant regime.

No comments:

Post a Comment